The Music of Kalevi Aho

By Dan Morgan

Kalevi

Aho (photo: Maarit Kytöharju/Fimic)

BIS supremo Robert von Bahr is one of the recording industry’s more

enterprising figures, combining so-called ‘core repertoire’ with contemporary

works. Among the latter is Finnish composer Kalevi Aho (b. 1949), most

of whose output has been recorded by BIS over the past two decades or

so.

Few living composers are fortunate enough to have the solid backing

of a single record label, not to mention the enthusiasm and support

of conductors such as Osmo Vänskä and John Storgårds.

This commitment and continuity ensures that Aho’s music is performed

in the best possible artistic and technical environment, whether it’s

the youthful

First Symphony (1969) or the ambitious

Twelfth

(2002-03).

Composer and performers

Kalevi Aho was born in Forssa, south-western Finland, in 1949. His musical

education began in earnest at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, where

he was taught composition by Einojuhani Rautavaara (b. 1928), considered

by many to be the greatest Finnish composer since Sibelius. Aho then

went on to lecture in musicology at the University of Helsinki, becoming

professor of composition at his

alma mater in 1988. Four years

later he was appointed the Lahti Symphony Orchestra’s composer-in-residence,

and since 1993 has devoted himself to composition.

Aho’s works and discography owe much to his longstanding relationship

with the Lahti band and their artistic director at the time, Osmo Vänskä.

Not only have the orchestra commissioned a number of his best works

they have also provided a standard of performance that most composers

can only dream of. Sadly Vänskä has since moved on to Minneapolis

and, at the time of writing (September 2008) has decided to relinquish

his position with the Lahti orchestra. That said the premiere and subsequent

recording of Aho’s

Twelfth Symphony suggests John Storgårds

will be as strong an advocate of this composer’s music as any.

In the concertos Aho is lucky enough to have some exceptional soloists,

among them Christian Lindberg (trombone), Sharon Bezaly (flute), Gary

Hoffman (cello), Lewis Lipnick (contrabassoon) and Martin Fröst

(clarinet). Throw in the BIS recording team and some good venues – Lahti’s

Ristinkirkko and Sibelius Hall – and you have the makings of a memorable

cycle. And there’s more to come, with von Bahr committed to recording

the rest of Aho’s works, most notably the

Fifth and

Sixth

Symphonies.

Receptive listeners should find much to enjoy here. Most established

genres are represented – symphonies, concertos, songs for orchestra

and chamber works – all of which highlight the consistency and strength

of Aho’s musical imagination. This composer seldom fails to engage and

hold one’s attention, especially in the symphonies, where he has a good

grasp of the long span and an uncanny instinct for instrumental colours.

But most of all one warms to the freshness and spontaneity of these

works.

Note: This survey covers the bulk of Aho’s output,

as recorded by BIS. Future releases and discs that also contain the

works of others will be reviewed individually on MusicWeb’s main site

– see the Additional reviews section at the end of this article. Links

to reviews by other contributors are included.

The recordings

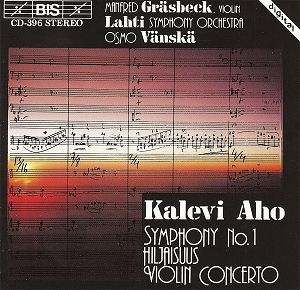

Symphony

No. 1

Symphony

No. 1 (1969)* [27:53]

Hiljaisuus (Silence) (1982) [4:56]

Violin Concerto (1981-82)** [27:38] *Sakari Tepponen – violin

solo (fourth movement) **Manfred Gräsbeck – violin Lahti Symphony

Orchestra/Osmo Vänskä rec. 29 May & 1 June 1989, Ristinkirkko

(Church of the Cross), Lahti, Finland

BIS CD 396 [61:45]

Given Sibelius’s reputation as one of the great symphonists of the last

century, contemporary Finnish composers may be forgiven for feeling

a little overshadowed. Fortunately for the young Aho, Rautavaara’s advice

and support proved decisive in shaping this symphony, which began life

as a string quartet.

The work is in four movements, the mysterious opening and ascending

brass figures of the Andante strongly reminiscent of Shostakovich.

Indeed, this is confirmed by the noted music publisher Fennica Gehrman,

in a short article on the Finnish Musical Information Centre

website.

There is no obvious programme here, but in his refreshingly unpretentious

liner-notes – a welcome feature of this entire cycle – Aho does speak

of ‘nightmares’ and ‘psychological crises’. Even without these pointers

the Andante has a certain bleakness – desolation, even – although there’s

none of the trenchancy one associates with Shostakovich in similar mood.

That said the grim little waltz in the Allegretto could so easily be

attributed to DSCH, not to mention the quiet but insistent tread in

the lower strings.

By contrast the Presto kicks off with an arresting

moto perpetuo

that drives this fugue like a musical dynamo.

This movement has some of the most individual writing so far. That said

the shade of Shostakovich hovers nearby, the laconic waltz tune and

a splintered remnant of the opening theme bringing the symphony to an

enigmatic close.

The other works on this disc –

Hiljaisuus (Silence) and the

Violin Concerto – date from the early 1980s. According to Aho,

Hiljaisuus,

a Finnish Radio commission that was to last no more than five minutes,

was intended as an introduction to the recently completed

Violin

Concerto. It’s a strange swirl of a piece, a mix of unsettling glissandos

and unearthly sonorities. Sample the short passage at 4:02 and you may

be forgiven for thinking you’re listening to Ligeti.

The

Violin Concerto has more momentum and contrast than

Hiljaisuus,

although it shares the latter’s concentrated, more dissonant idiom.

It isn’t the most grateful start to a violin concerto, the solo part

– sensitively played by Manfred Gräsbeck – rather less prominent

than one might expect. That said it would be difficult to hear it above

the orchestral eruptions that punctuate the first movement.

At 8:30 the soloist is given some insistent phrases that rise above

muted timps, culminating in an equally restrained close.

The repeated phrases at the start of the second movement – marked Leggiero

– lead into music that fluctuates between light and shade. The soloist

has some rhapsodic passages all to himself before we plunge into the

spectral waltz of the finale.

La Valse this isn’t, but

the wild, somewhat demonic element is certainly present. Gräsbeck

phrases these tunes like a Mahlerian

Ländler – listen to

the passage beginning at 3:37 – before he is crushed by a massive orchestral

climax worthy of Bartók in

Miraculous Mandarin

mode.

Whatever hints there may be of other sound worlds Aho has fashioned

something altogether individual here, combining a range of ear-pricking

sonorities with music of considerable punch and power. Nothing quite

prepares one for the gentle, introspective close to this concerto which,

as I have discovered, is something of an Aho trademark.

Despite its obvious influences the symphony is remarkably assured for

a student work. It’s economically scored, light on its feet and direct

in its appeal, the chamber-like qualities much enhanced by the airy

recording. The concerto is more roughly hewn; it’s a protracted tussle

between soloist and orchestra, yet it has real presence and power. All

credit to the Lahti Symphony Orchestra – just 40 years old when this

recording was made – who play these scores with commitment and care.

An excellent

entrée to Aho’s distinctive sound world.

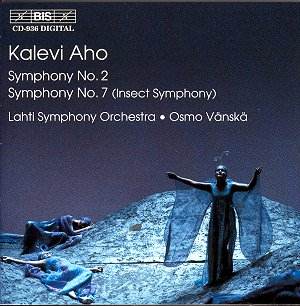

Symphony

No. 2 (1970/1995) [21:14] Symphony No. 7 ‘Hyönteissinfonia’

(Insect Symphony) (1988) [46:03] I. The Tramp, the Parasitic Hymenopter

and its Larva [7:04] II. The Butterflies (The Foxtrot and Tango of the

Butterflies) [4:33] III. The Dung Beetles (Grief over the Stolen Ball

of Dung) [3:52] IV. The Grasshoppers [6:11] V. The Ants (The Working

Music of the Ants and War Marches I and II) [11:13] VI. The Dayflies

and Lullaby for the Dead Dayflies [12:45] Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo

Vänskä rec. January 1998, Ristinkirkko, Lahti, Finland

BIS CD 936 [68:17] see also

review [PGW]

Symphony

No. 2 (1970/1995) [21:14] Symphony No. 7 ‘Hyönteissinfonia’

(Insect Symphony) (1988) [46:03] I. The Tramp, the Parasitic Hymenopter

and its Larva [7:04] II. The Butterflies (The Foxtrot and Tango of the

Butterflies) [4:33] III. The Dung Beetles (Grief over the Stolen Ball

of Dung) [3:52] IV. The Grasshoppers [6:11] V. The Ants (The Working

Music of the Ants and War Marches I and II) [11:13] VI. The Dayflies

and Lullaby for the Dead Dayflies [12:45] Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo

Vänskä rec. January 1998, Ristinkirkko, Lahti, Finland

BIS CD 936 [68:17] see also

review [PGW]

The Second Symphony is also a youthful work

– the composer was just 21 at the time – but it differs from the First

in that it’s cast in a single movement. After the premiere in 1973 Aho

decided to rework the middle section, a task he didn’t attempt until

1995. The result is a compact, tightly structured piece – it’s a triple

fugue – which the composer candidly admits was intended as an antidote

to some of the more ‘difficult’ music of the 1960s.

As with the fugues in the First Symphony there’s no hint of dutifully

reconstructed baroquerie or dry didacticism; instead, Aho uses fugues

to create a remarkably dramatic and cohesive symphonic whole.

And despite the echoes of Shostakovich in the First Symphony

it would be wrong to think of Aho’s early musical style as ‘Shostakovich-lite’.

Yes, DSCH could be the model for the brooding theme that ushers

in the Second Symphony but there is enough in this unfolding

music to suggest the composer is finding his own ‘voice’. Just listen

to that extraordinary sustained passage that begins at 10:03,

where we enter a more individual, more rarefied soundscape altogether.

There is a pleasing directness to Aho’s musical utterances that will

appeal to those who find much late-20th-century music too

dry or relentless. Even though this symphony may only last 20 minutes

there is much to discover and enjoy here. As always Vänskä

and his Lahti band – the mainstays of this cycle – are very well recorded,

especially in the symphony’s final, more spectral, moments.

This well-filled disc also offers a splendid performance of Aho’s Seventh

Symphony, penned after the composer took a break to concentrate

on his concertos and other works. The intriguing subtitle, ‘Insect Symphony’,

is derived from the composer’s opera Insect Life, which he entered

for a Savonlinna Opera Festival competition in 1988. The work was rejected

at the time, so rather than abandon it altogether Aho decided to recast

it as a symphony. Incidentally, Savonlinna’s loss was Helsinki’s gain,

as Insect Life was given a triumphant premiere by Finnish National

Opera in 1996.

The result is a set of six pieces that contain conventional musical

forms, including a foxtrot, tango, marches and lullaby. The first movement,

‘The Tramp, the Parasitic Hymenopter and its Larva’, takes its cue from

the opera’s only human character, a drunk vagrant who anthropomorphises

the insects he encounters. Investing them with human feelings and foibles

is not as twee or Disneyfied as it may seem; indeed, Aho provides music

of considerable wit and character here.

The tipsy brass and bass-drum pratfalls of the first movement are nicely

done,

and despite the episodic nature of this work Aho manages to weld the

sections into a fairly convincing symphonic whole. There is music of

real virtuosity throughout that calls for contributions from solo piccolo,

flute, trumpet, tuba and cello. Naturally, the deliciously louche ‘Foxtrot

and Tango of the Butterflies’ demands an alto sax, stylishly played

by Hannu Lehtonen. It’s infectious stuff, the rhythms as sharp as a

razor.

The tango especially has a sultry charm that is most enjoyable, the

players clearly relishing the chance to let their hair down a little.

The somewhat ungainly sounds of the next movement manage to suggest

the squat shape of the hard-working dung beetles. I suppose one could

argue that this is the kind of workaday accompaniment one might expect

from an Attenborough documentary but really you’ll find nothing there

that is as accomplished as this. You won’t hear crude musical imitation

in ‘The Grasshoppers’ either; even though there is an appropriate chirpiness

to the writing here.

The martial rhythms of the working ants are subtly done, with fine contributions

from the Lahti brass and percussionists. It’s strong, muscular music

that never breaks its stride, the sheer range of Aho’s colour palette

very impressive indeed. And there’s a satirical edge to these marches

that Shostakovich would surely have enjoyed. Just listen to the gong’s

long, slow decay into silence at the end of this movement, a simple

device but hair-raising nonetheless.

Aho is in a much more reflective mood when it comes to the short-lived

dayflies. Is there a philosophical dimension to this movement? Perhaps;

the music certainly has a fleeting, evanescent quality that is most

apt. Aho’s melodic strengths are very much in evidence here, the music

unfurling like the passing hours. It’s not all wistfulness – there are

some splendid climaxes too – but the symphony does draw to a gentle,

reflective close. Aho provides music of great tenderness and beauty

here, an extended lament, moving in its simplicity.

Even though the composer can’t quite disguise the ‘bitty’ nature of

this score – one could argue that it’s more of a suite than a symphony

– it is bound together by music of great originality and charm. Kudos

to all involved, especially the BIS engineers, who have produced another

astounding disc. Not to be missed.

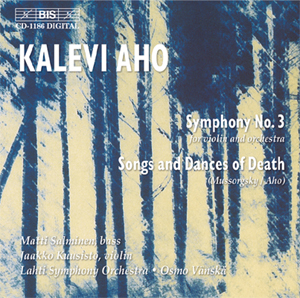

Symphony

No. 3 (Sinfonia Concertante) (1971/1973)* [38:23] Songs and Dances

of Death (Modest Mussorgsky, arr. and orch. Aho) (1984)** [19:58]

*Jaakko Kuusisto (violin) **Matti Salminen (bass) Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo

Vänskä rec. 17 & 19 February 2001 (symphony), 12 May 2000

(Mussorgsky), Sibelius Hall, Lahti, Finland BIS CD 1186

[59:41]

Symphony

No. 3 (Sinfonia Concertante) (1971/1973)* [38:23] Songs and Dances

of Death (Modest Mussorgsky, arr. and orch. Aho) (1984)** [19:58]

*Jaakko Kuusisto (violin) **Matti Salminen (bass) Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo

Vänskä rec. 17 & 19 February 2001 (symphony), 12 May 2000

(Mussorgsky), Sibelius Hall, Lahti, Finland BIS CD 1186

[59:41]

If Aho uses fugues to forge a link between his music

and that of earlier periods he does the same with this symphony, subtitled

‘Sinfonia Concertante’. A classical conceit – Mozart’s K.364 is probably

the best known example – this admixture of concerto and symphony has

persisted through the 19th century and into the 20th.

Latter proponents of the genre include Prokofiev, Martinů and Walton.

In his liner-notes Aho admits the Third Symphony was intended

as a violin concerto but it metamorphosed into a sinfonia concertante,

the first movement of which – a darkly expressive Andante – is dominated

by the soloist.

But it’s the muted timps that make the most impact at the outset, surely

reminiscent of the start of Shostakovich’s bleak Symphony No. 11,

‘The Year 1905’.

That said the violin rises out of the mists in a songful display. The

Finnish violinist, Jaakko Kuusisto, fends off the encroaching orchestra

with some lovely, understated playing. The distinctly martial mood of

the Prestissimo doesn’t drown out the soloist completely, although there

are some impressive drum thwacks here. Sensibly the BIS engineers haven’t

gone for a hifi spectacular, but have produced a recording of considerable

range and sonic impact.

As always, though, it is the astonishing detail of Aho’s score that

registers most clearly. The Lahti band play very well indeed – just

listen to the superbly articulated brass at 6:23, baying first and snarling

later.

Throughout Vänskä manages a good balance between momentum

and weight on the one hand and detail and colour on the other. The movement

ends with a long, breathtaking crescendo for snare and bass drums.

The Lento may seem like an oasis of calm after the turbulence of the

previous movement but there is still a restlessness, a sense of disquiet.

It’s not the highly strung – some might say histrionic – anxiety one

associates with Shostakovich; no, it’s altogether more controlled, stoic

even, with an implacable tread that’s surely more Sibelius than Shostakovich.

However, the bells at 7:03 bring to mind the tocsins (alarm bells) of

‘The Year 1905’. Once again Aho – still in his early 20s

at the time – surprises with music of astonishing eloquence and beauty,

as in the lovely string passage that begins at 7: 28.

The fourth movement – marked Presto – reprises the muted opening of

the first movement, the soloist dissembling briefly before the menacing

martial rhythms return. Ensemble is crisp and clear throughout, the

Sibelius Hall providing just enough warmth without clouding all-important

details. It really is an exemplary recording and proof, if it were needed,

that good production values can significantly enhance one’s enjoyment

of music, especially when it comes to new and unfamiliar repertoire.

The filler is Aho’s arrangement and orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Songs

and Dances of Death (1875-77). Of course Mussorgsky is no stranger

to such things – witness Rimsky’s ‘version’ of Boris Godunov

and no less than 28 orchestrations of Pictures at an Exhibition

– and this song cycle is no exception. Rimsky and Glazunov prepared

an orchestral score from the piano original but the dark intensity of

these death-obsessed songs is best realised in Shostakovich’s 1962 reworking

of the score.

The baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky recorded the latter version with Yuri

Temirkanov and the St. Petersburg Philharmonic (Warner Classics 2564

62050-2), which I have used for comparison. Arguably his voice is not

quite dark enough for these songs – Aho’s version was written in response

to a request from the formidable Finnish bass Martti Talvela – but it’s

the orchestration that is of real interest here. In the CD booklet Aho

says he strived to preserve the work’s character while enhancing it

with what he calls ‘psychological instrumentation’. An interesting strategy,

risky even, but does it work?

These four songs deal with a mother’s desperate attempts to protect

her child, Death’s flirtation with a pale young woman, a drunken tramp

collapsing in the snow and Death summoning his armies on the battlefield.

Shostakovich’s response to ‘Cradle Song’ is unmistakable, from the winding

cello theme at the outset to those bell-like sounds that seem to mark

the passing hours. It’s surprisingly austere, Aho’s version perhaps

more overt – theatrical even – with greater dynamic and emotional contrasts.

That said Shostakovich’s arrangement has a marrow-piercing chill that

is hard to beat.

Death’s ‘Serenade’ isn’t as erotically charged as it might be in Aho’s

version but then I wasn’t particularly convinced by Matti Salminen’s

vocal characterisation either.

In comparison Hvorostovky has an arrogance, a virility, that is much

more appropriate to this cruel seduction. Orchestrally Shostakovich

pares the music down to its essentials, not a note, rhythm or nuance

wasted. Just listen to Death’s triumphant cry at the end, underpinned

by a simple timp stroke; Aho opts for a swirling harp and mighty drum

thwack, which is much less subtle.

In ‘Trepak’ Salminen – who is never less than polished, if sometimes

a little bland – sings with vigour and intelligence. He is suitably taunting here, Aho’s orchestration exotic and larger

in scale than Shostakovich’s. But, and it’s a big but, it’s the latter’s

biting, more sardonic scoring that is most telling here.

Similarly Shostakovich’s Field Marshal is vocally more communicative,

the grim, bell-like orchestral figures tolling to great effect. At the

start Aho’s powerful drums are exciting but again one feels that in

this case less really is more. As a virtuoso vocal and orchestral display this piece certainly

has its merits but if you want to get to the dark heart of these songs

Shostakovich knows the way.

A mildly disappointing disc, on account of the Mussorgsky, but the symphony

certainly confirms Aho’s growing confidence in the genre. Other influences

may still be discernible but they are gradually being supplanted by

music that is distinctively his own. One of the characteristics of these

symphonies that I particularly relish is his ability to surprise and

seduce when one least expects it.

As always, Vänskä and his Lahti band are in fine fettle, the

recording a model of clarity and warmth. Not perhaps the finest disc

in the cycle but well worth exploring nonetheless.

Kiinalaisia lauluja (Chinese Songs) (1997)* [18:07] I. Punainen

aurinko (The Red Sun) (Text: Li Yü) [2:20] II. Miten taipuisa (How

Pliant) (Text: Cho Wen-chün) [2:21] III. Kultainen lintuhiusneula

(The Golden Bird Hairpin) (Text: Li Yü) [2:22] IV. Yöllä,

aivan päihdyksissä (At Night, Very Drunk) (Text: Li Ch´ing-chao)

[3:37] V. Syksyn tuuli (The Wind of Autumn) (Text: Li Yü) [4:20]

VI. Lumen keskellä kevään viesti (Amid the Snow, the

Message of Spring) (Text: Li Ch´ing-chao) [3:02] Symphony No. 4

(1972-73) [44:20] *Tiina Vahevaara (soprano) Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo

Vänskä rec. June 1999, Ristinkirkko, Lahti, Finland BIS

CD 1066 [63:19]

Kiinalaisia lauluja (Chinese Songs) (1997)* [18:07] I. Punainen

aurinko (The Red Sun) (Text: Li Yü) [2:20] II. Miten taipuisa (How

Pliant) (Text: Cho Wen-chün) [2:21] III. Kultainen lintuhiusneula

(The Golden Bird Hairpin) (Text: Li Yü) [2:22] IV. Yöllä,

aivan päihdyksissä (At Night, Very Drunk) (Text: Li Ch´ing-chao)

[3:37] V. Syksyn tuuli (The Wind of Autumn) (Text: Li Yü) [4:20]

VI. Lumen keskellä kevään viesti (Amid the Snow, the

Message of Spring) (Text: Li Ch´ing-chao) [3:02] Symphony No. 4

(1972-73) [44:20] *Tiina Vahevaara (soprano) Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo

Vänskä rec. June 1999, Ristinkirkko, Lahti, Finland BIS

CD 1066 [63:19]

Mahler’s Chinese settings in Das Lied von der Erde

spring to mind here, Anne Weller noting that Aho chose his texts for

their ‘joie de vivre ... combined with the transitory nature

of life’. Mahler would certainly understand these sentiments and, yes,

there is a hint of late-Romantic weltschmerz here too.

The opening of ‘The Red Sun’ – the six songs are grouped in three pairs

played without breaks – surely echoes the first of Korngold’s bittersweet

Abschiedlieder. It’s a fleeting resemblance and Aho brings his

own, lightly perfumed harmonies to bear. The soprano, Tiina Vahevaara,

sings with commendable passion, although some listeners may find her

a little too steely under pressure.

As always Aho manages a seamless transition to the next song, ‘How Pliant’,

which speaks of love and how to preserve and prolong those fleeting

moments – ‘May this year last ten thousand times longer!’

Aho deftly blends the scented imagery of these poems with music of economy

and restraint. Yet there is a charge, a tension, in this song that Vahevaara

captures rather well with her transported singing. In ‘The Golden Bird

Hairpin’ we are made keenly aware of the passing of time – ‘At the moment

of night the water clock stops’ – and the mood continues to darken in ‘At Night, Very Drunk’. There

is a marvellous, tremulous quality to the orchestral writing here, a

heightened sensitivity to the song’s mood of growing despair.

In the final pairing, ‘The Wind of Autumn’ and ‘In the Snow, the Message

of Spring’, Aho adds a certain chill to the first with music that swirls

around and lifts the vocal line; the final song opens with a bright,

tolling figure, this time amidst a flurry of snow.

At last the intervention of a benign deity brings new-found joy – ‘Now

we drink wine from deep golden goblets!’ – and Aho responds with music

of some vigour and weight. It’s not the most grateful of parts – more

a kind of oriental vocalise – but Vahevaara acquits herself well in

the work’s more ecstatic moments.

We now step back a quarter century to Symphony No. 4 (1972-73).

Fennica Gehrman, whose FIMIC essay I referred to in my introduction,

believes this symphony marks the end of Aho’s so-called ‘early period’.

Indeed, even a cursory audition of this score suggests a shift in the

composer’s musical landscape. Not seismic, perhaps, but significant

nonetheless.

Begun while the composer was on a scholarship to Berlin, the Fourth

Symphony was only completed on his return to Finland in 1973. Not

surprisingly it has a fugal theme in the first movement that resonates

throughout. The gentle opening of the Adagio sounds wonderfully poised

and translucent, before descending via the lower strings to a less idyllic

plane. There is a palpable tension here, the sudden brass fanfare at 4:14

echoed shortly afterwards, before the timps confirm this growing sense

of unease.

As always with this composer there is a remarkable compactness, a simplicity

of design, that is lyrical and heartfelt. More important there is a

cumulative energy in this Adagio, a thrust and intensity, that we’ve

not heard before. Yes, the transported trumpets may remind you of Shostakovich,

but it’s the melancholy string theme at 10:00 that is most striking,

the long, expressive lines very moving indeed.

The original fugal theme is continually tossed about in this lengthy

movement, yet the music doesn’t outstay its welcome. Vänskä

is particularly adept at maintaining tension throughout, never allowing

the players to lose focus or momentum. Typically the Adagio ends with

one of Aho’s lovely string melodies, fading slowly into silence. Very

atmospheric indeed.

The excitable Allegro – Presto is chockful of ear-pricking detail, the

playing wonderfully supple and precise. It really is remarkable how

the composer deploys that germinal theme in such original ways. And

at 4:45, surely that busy little theme brings Prokofiev to mind? Certainly

there is a motoric element to this music that the latter would have

recognised. There is a real frisson of excitement at the long, pounding

peroration that ends this movement. Goodness, this is terrific music

making, crowned with some visceral – and well recorded cymbal clashes.

The half-lit Lento is altogether different. There is a dirge-like quality

at the outset that steers well clear of lugubriousness. Once again I had to admire the composer’s melodic and harmonic gifts,

not to mention his ability to shift the mood so seamlessly. Listen to

that circus-like fanfare at 8:07. In other hands it may seem incongruous

but in Aho’s it sound entirely apposite. And that, surely, is the sign

of a composer firmly in control of his material.

An exhilarating symphony this, and another triumph for Vänskä,

his players and the BIS engineers. Even in an age of high-resoution

recordings this must count as one of the finest recordings in the cycle.

The Chinese Songs are a desirable filler, but as with the Songs

and Dances of Death I remain somewhat ambivalent about Aho in vocal

mode. But the symphony’s the real draw here, and that I can heartily

recommend.

Symphony No. 5 (1975-76) & Symphony No. 6 (1979-80)

At the time of writing (September 2008) neither of these symphonies

has appeared on BIS. In the case of the Sixth, there don’t appear

to be any commercial recordings at all. However, there is a fine version

of the Fifth – coupled with the ‘Insect Symphony’ – from Max

Pommer and the Leipzig radio orchestra (Ondine ODE 765). Read my colleague

Tim Perry’s enthusiastic review here.

Symphony No. 8 for organ and orchestra (1993)* [50:07] Pergamon,

for four orchestral groups, four narrators and organ (1990)** [10:29]

*Hans-Ola Ericsson (organ) **Lilli Paasikivi, Eeva-Liisa Saarinen, Tom

Nyman and Matti Lehtinen (narrators); Pauli Pietiläinen (organ)

Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo Vänskä rec. 23-25 May 1994,

Ristinkirkko, Lahti, Finland BIS CD 646 [61:54]

Symphony No. 8 for organ and orchestra (1993)* [50:07] Pergamon,

for four orchestral groups, four narrators and organ (1990)** [10:29]

*Hans-Ola Ericsson (organ) **Lilli Paasikivi, Eeva-Liisa Saarinen, Tom

Nyman and Matti Lehtinen (narrators); Pauli Pietiläinen (organ)

Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo Vänskä rec. 23-25 May 1994,

Ristinkirkko, Lahti, Finland BIS CD 646 [61:54]

This work, one of many commissions from the Lahti Symphony

Orchestra, is Aho’s very own ‘Organ’ Symphony. A densely packed piece

in eight movements it’s also rougher and more angular than the earlier

symphonies, with great cliffs of sound alternating with quieter, more

intimate moments that recall his earlier works.

‘The tragedy of society and the individual, and its musical setting’,

the title of Anne Weller’s booklet essay, gives one an idea of what

to expect from this music. And although the Eighth marks a somewhat

traditional journey from innocence to experience, what is less traditional

is Aho’s musical language, which is much more uncompromising than before.

Dissonances are plentiful, the organist playing a series of cadenzas

in the three interludes, while adding colour and weight elsewhere.

For once I couldn’t think of a comparable sound world, such is the individuality

of Aho’s writing here. The opening of the Introduction starts at both

frequency extremes; it’s a strange effect and the first of many in this

work.

The first somewhat manic Scherzo displays a growing tension that erupts

in a series of confrontations between organ and orchestra. Aho intersperses

these conflicts with quietly rhythmic – yet restless – episodes.

It’s curiously unsettling music, exacerbated by the organ’s virtuoso

display in the first Interlude and the strident dissonance that opens

the second Scherzo. There is still plenty of instrumental detail audible

but nothing prepares you for the epic battle that begins at 3:26. Remarkably

Vänskä keeps his forces on track and the engineers never allow

the music to slide into incoherence. This is demonstration material

that will surely tax even the best sound systems.

Aho knits these movements together with considerable skill, so that

the bells and organ at the end of the second Scherzo act as an effective

‘bridge’ between it and the ensuing Interlude. Ditto the transition

from this Interlude to the ferocious music of the third Scherzo.

If it’s spectacle you want just listen to the passage that begins at

7:46 in this third and last Scherzo; it’s a shattering stand-off between

organ and timps, fading to a simple yet reassuring Interlude. (And yes,

there’s another one of those near miraculous transitions here too.) Indeed,

there is a hypnotic calm here – a sense of spirituality, perhaps – that

may well remind listeners of Messiaen at his most contemplative.

Organist Hans-Ola Ericsson plays with great sensitivity throughout and

in the Epilogue the low-frequency rumble of the instrument as it underpins

the orchestra is superbly balanced by the BIS engineers. Now the agitated

timps are supplanted by gentle beats below organ glissandi, the battle

hard fought and hard won. It’s this unfailing ability to ambush his

listeners that makes Aho’s scores so fascinating.

Organist Hans-Ola Ericsson plays with great sensitivity throughout and

in the Epilogue the low-frequency rumble of the instrument as it underpins

the orchestra is superbly balanced by the BIS engineers. Now the agitated

timps are supplanted by gentle beats below organ glissandi, the battle

hard fought and hard won. It’s this unfailing ability to ambush his

listeners that makes Aho’s scores so fascinating.

Pergamon, written for the 350th

anniversary of Helsinki University in 1990, is based on the so-called

Pergamon Altar that dates from the 2nd century BC. It’s an

extraordinary edifice, with a 371ft frieze depicting the battle between

the gods (in human form) and the giants (fallen angels). (Photo courtesy

of G. Ray Thompson

Salisbury University click for enlarged version) This gigantomachy,

reconstructed in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum, gives Aho plenty of scope

for thrilling orchestral effects, starting with that massive gong and

drum smash and ensuing organ pedal.

But there’s more to this piece than simple sonics. The texts, by the

German writer Peter Weiss (1916-82), who fled Nazi Germany and settled

in Sweden, are spoken in German, Finnish, Swedish and Ancient Greek.

The four narrators are arranged around the auditorium, their declamations

swirling about the hall. Clearly Aho is fascinated by spatial music, an interest that culminates

in his ‘Luosto’ Symphony, premiered on a mountainside.

Given Weiss’s antipathy to the Nazis his response to this great battle

has obvious resonances. For his part Aho creates a most unusual work,

the voices sandwiched between music that roars and shrieks at both frequency

extremes. In between there is much to delight the ear; just listen to

that strange glissando that begins at around 3:12.

Even though this is one work that needs to be heard live the BIS engineers

have done a remarkable job capturing the essence of this ambitious score.

As ever the Lahti band play with great concentration and produce some

spine-tingling sounds along the way. And while the piece has its apocalyptic

moments – sample the passage beginning at 7:16 – the composer’s judicious

use of orchestral effects ensures Pergamon never becomes bombastic

or vulgar. A terrific filler and a splendid piece in its own right.

Altogether a very successful coupling.

Symphony

No. 9 for trombone and orchestra (1993-94)* [31:19] Concerto

for cello and orchestra (1983-84)** [29:39] *Christian Lindberg

(trombone) **Gary Hoffman (cello) Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo Vänskä

rec. 9-10 January 1995 (symphony), 7-8 September 1993 (concerto), Ristinkirkko,

Lahti, Finland BIS CD 706 [61:59]

Symphony

No. 9 for trombone and orchestra (1993-94)* [31:19] Concerto

for cello and orchestra (1983-84)** [29:39] *Christian Lindberg

(trombone) **Gary Hoffman (cello) Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo Vänskä

rec. 9-10 January 1995 (symphony), 7-8 September 1993 (concerto), Ristinkirkko,

Lahti, Finland BIS CD 706 [61:59]

Hard on the heels of the Eighth comes another hybrid – Aho originally

called this work Sinfonia concertante No. 2 – with the

trombonist flamboyantly adding his distinctive timbre to the orchestral

mix and giving voice to the work’s inner tensions.

In her liner-notes Anne Weller points out that the Eighth and

Ninth symphonies – paired at the latter’s premiere – are musical

opposites, one dark the other light. A quick run-through of the Ninth

rather confirms this, with Christian Lindberg’s mellifluous entry in

the first movement quite without angst or aggression. Even the animated

orchestration suggests an altogether more optimistic mood. In fact just

listen to the passage that begins at 2:44, a lightly sprung piece of

baroquerie with some beautifully articulated playing from the soloist.

As I mentioned in my review of the First Symphony Aho seems to

see himself as part of a great musical tradition; the Ninth is

no exception, combining contemporary sonorities and melodic juxtapositions

with formal elements from the past. Aho manages this very well, the

various elements blended with great naturalness and skill. Far from

seeming an odd progression the first movement, Presto, presents us with

an invigorating musical collage, passages of Beethovenian thrust and

energy jostling with late 20th century timbres and dissonances.

It’s a heady mix but Vänskä, Lindberg and the Lahti band despatch

it with great virtuosity.

Even the three mighty drum thwacks at the end of the first movement

can’t dispel the music’s more genial mood, especially in the Adagio

that follows. Lindberg’s playing here is very impressive indeed, the

elegiac trombone rising over a grumbling bass.

Another one of Aho’s rather magical slow movements, but it’s not without

music of a more uncompromising nature. Yes, taken at face value this

may be a sunnier piece but there is still an inner dialectic here –

witness the collision of trombone and orchestra. And at 8:19 you may

be forgiven for thinking you were listening to a sackbut as the music

slides seamlessly into late Renaissance/early Baroque mode.

The most ebullient music belongs to the third movement, whose opening

Presto has real sparkle and sprightliness. As always Lindberg’s virtuosic

playing is first-rate, in what seems to be a good-natured tussle with

the drum-dominated orchestra. No existential angst here, just writing

of great skill. For a bit of fun just listen to the tipsy trombone passage

that begins at 3:37. This is music written – and played – with plenty

of humour. Vänskä brings it all to a triumphant close.

By contrast the Cello Concerto is a much spikier, more unforgiving

work. That’s clear from the cello’s opening melody and the orchestra’s

dark, sustained dissonances. Glissandos abound in the orchestra, creating

a remarkable sense of ‘otherness’, with only the ghostliest of rhythms

emerging at 2:50 in the first movement.

The cellist, Canadian-born Gary Hoffman, is convincingly recorded, combining

warmth with detail.

There is a Godot-like sense of alienation in this oblique ‘dialogue’

between soloist and orchestra, with a slow-burning but increasingly

powerful passage that begins at 4:18. That said the music takes on a

rollicking gait as well, this flash of humour soon subsumed by the weightiest

of perorations.

The first movement ends with an extended, more reflective passage for

the soloist before evaporating with a gentle shimmer. There is nothing

enigmatic about the powerful, stabbing rhythms that launch the second

movement. This is writing of great power and concentration, a foil to

the extended – and virtuosic – solo cadenza that follows.

In the end, though, it is the orchestra that triumphs with a roof-raising

climactic passage that begins at 11:03. Once again I could only marvel at the depth and scale of this recording,

it really is astonishing. But there is always a surprise in store and

rather than end with a bang the concerto ends with a whimper, fading

out just as the first movement faded in.

Not an easy listen, this. One may flinch at the wide dynamic range of

Aho’s score but there’s no doubt the composer has absolute control of

his material. Vänskä also knows where this music is going

and delivers what must surely be a benchmark reading of this wild and

wonderful work.

Syvien

vesien juhla, fantasia orkesterille (Rejoicing of the Deep Waters, fantasy

for orchestra) (1995) [11:03] Symphony No. 10 (1996) [46:54]

Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo Vänskä rec. March 1996 (fantasy),

February 1997 (symphony), Ristinkirkko, Lahti, Finland BIS CD 856

[58:44]

Syvien

vesien juhla, fantasia orkesterille (Rejoicing of the Deep Waters, fantasy

for orchestra) (1995) [11:03] Symphony No. 10 (1996) [46:54]

Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo Vänskä rec. March 1996 (fantasy),

February 1997 (symphony), Ristinkirkko, Lahti, Finland BIS CD 856

[58:44]

Aho’s opera Insect Life may have been rejected at first but that

didn’t stop him dabbling in the genre. Rejoicing of the Deep Waters

is based on his opera, Before We All Have Drowned, which has

since been performed in Helsinki and Lūbeck. And even though it

was written for the city of Lahti’s 90th anniversary it’s

certainly not celebratory in tone. In fact the work begins with a lovelorn

surgical nurse throwing herself off a bridge, the ensuing story told

in a series of flashbacks.

There is certainly a dramatic thrust to this score, yet it is framed

in a surprisingly conventional musical idiom. And despite the seemingly

grim plot there is little Nordic angst on show here, confirmed by the

music’s almost classical restraint and sense of proportion. Indeed,

it’s just like a conventional overture, with a discernible dramatic

‘arch’, and if it has a message it’s in the final words of the opera:

‘Listen, so that you learn to listen / and save us / before we are all

drowned.’ It makes an attractive, if lightweight, curtain raiser to

the more substantial symphony that follows.

Speaking of classical structures, Aho’s Tenth Symphony – a joint

commission from the Lahti Symphony Orchestra and the Finnish Association

for Mental Health – has its origins in a performance Aho heard of Mozart’s

Symphony No. 39, played by the Lahti band. An intriguing source

of inspiration, perhaps, but not one that readily comes to mind when

listening to this towering score.

Admittedly, as Anne Weller points out in her liner-notes, Aho only uses

the first three notes of the Mozart symphony’s main theme to launch

his Tenth Symphony. The Allegro certainly starts off with some

delicacy and charm

but it’s soon clear this is not going to be a sunny work. The ever-present

timps rumble like distant thunder as we move into a darker, gong-tormented

world and back into another, more elegant, lightly sprung phase. Throughout

there is an admirable clarity and lightness of step that is most appealing.

As always Aho is a master of unusual contrasts and unexpected timbres.

The extra resources required – among them soprano and alto trombones

and a piccolo clarinet – give you some idea of the work’s colour palette.

The Prestissimo has some fevered string playing against a rather ghostly

background.

It’s unsettled – and unsettling – with a macabre rattling figure underlining

it all. Macabre would certainly be one way of describing the mood of

this movement, whose timps and-tam tam rear up from time to time.

It’s not nearly as uncompromising as it sounds. Indeed, out of the turmoil

arises a luminous little melody that takes us to the end of the Prestissimo

and segues neatly with the yearning string theme that begins the 20-minute

Adagio. This is music of great intensity, not a million miles from the

innig Adagios we associate with Mahler.

Not only that, there is a wonderful transparency to the writing here

that also reminds me of Mahler, albeit with Aho’s own imaginative touches.

Don’t expect angst, for this Adagio is shot through with passages of

great poise and tenderness. Extraordinarily, Aho binds these disparate

sound worlds into a very convincing whole, the hushed playing of the

Lahti band riveting throughout. And the peroration that begins to build

at 8:42 has an unmistakable, echt-Mahlerian feel, matching weight

with detail. Most importantly this symphony never postures or lapses

into empty rhetoric; indeed, Aho’s unfailing directness and drive are

what make this music so invigorating.

Yes, there is a series of cataclysms – shrieking clarinets and timps

– yet Aho does ‘modulate out of the key of self-abasement – to borrow

Forster’s phrase – into something more stoic, noble even. And what an

extraordinary climax to this movement, a long fade to silence, followed

by a quirky, virtuosic Vivacissimo.

Again I was struck by the natural perspectives and balances in this

recording. It’s the sound one might hear from a good seat in the stalls.

Longueurs? Vänskä makes sure there aren’t any. And just when

you think the end is in sight Aho throws in another eruptive passage

that carries the symphony to its powerful close. Stirring stuff, adroitly

done.

Symphonic

Dances (Hommage à Uuno Klami) (2001) [27:39] I. Prelude

[3:13] II. Return of the Flames and Dance [4:53] III.

Grotesque Dance [5:15] IV. Dance of the Winds and Fires [13:56]

Symphony No.11 for six percussionists and orchestra (1997-98)*

[31:42] *With the Kroumata Percussion Ensemble Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo

Vänskä rec. January 2002 (Symphonic Dances), February

2002 (Symphony No. 11), Sibelius Hall, Lahti, Finland BIS

CD 1336 [60:09]

Symphonic

Dances (Hommage à Uuno Klami) (2001) [27:39] I. Prelude

[3:13] II. Return of the Flames and Dance [4:53] III.

Grotesque Dance [5:15] IV. Dance of the Winds and Fires [13:56]

Symphony No.11 for six percussionists and orchestra (1997-98)*

[31:42] *With the Kroumata Percussion Ensemble Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo

Vänskä rec. January 2002 (Symphonic Dances), February

2002 (Symphony No. 11), Sibelius Hall, Lahti, Finland BIS

CD 1336 [60:09]

The Symphonic Dances are derived from Pyörteitä

(Whirls) an unfinished ballet by Uuno Klami (1900-61). In his detailed

liner-notes Aho explains that he orchestrated the first and second acts

(available on BIS CD 656) and was then asked to write the music for

the missing Act III. However, plans for the ballet came to nought, so

Aho retitled the work for concert performance.

Pyörteitä is based on part of that epic of Finnish

and Karelian folklore, the Kalevala, which inspired no less than 12

works by Sibelius. Klami’s ballet focuses on the forging of the Sampo,

which Aho describes as a ‘magical object that brings eternal happiness

and prosperity’. In the first act Ilmarinen the smith can’t quite make

the genuine article, no matter how much his slaves stoke the furnace.

Act II, set in space, features a number of astral dances, and in the

climactic third act Ilmarinen and his minions harness the power of the

winds and finally create the Sampo.

Powerful stuff and a marvellous opportunity for Aho to let rip. Indeed,

my review copy of this disc was plastered with stickers extolling its

sonic virtues. The Prelude opens with bells and swirling harps, before

slipping into music of real vigour and bite. Listeners may be reminded

of other ballets – Stravinsky’s Firebird and Prokofiev’s Ala

and Lolli perhaps – but as always Aho gives this music a distinctive

flavour of its own.

As for the recording, it certainly lives up to the promotional hype.

There is detail aplenty and the climaxes expand without a hint of strain.

I was particularly impressed by the depth of the soundstage, which creates

a more ‘layered’ sound, allowing one to hear inner detail. It’s certainly

motoric – sample the passage beginning at 1:37 – but this exhilarating

score manages to combine fluidity with power. It really is music that

cries out to be danced to.

The ‘Grotesque Dance’ brings together lurid sounds – listen to those

brass whoops at 4:09 – and moments of surprising tenderness before the orchestral gales

begin to blow in the ‘Dance of the Winds and Fires’. Once again I was

struck by the sheer inventiveness of this score, which has plenty to

please the ear and set the pulse racing. Special thanks to the musicians

and conductor, who inject just enough adrenaline into a score that could

so easily sound overblown. And just in case you think it’s all too driven

listen to this lovely postlude that begins at 11:30. Simply gorgeous.

Originally a commission from the Swedish Concert Institute the Eleventh

Symphony was to include the Kroumata Percussion Ensemble. Anyone

who has sampled the latter’s discs will know they are an exceptional

band. As Aho relates in his liner-notes he took the time to visit them

during the compositional process. The work was premiered by the Lahti

orchestra on 10th March 2000, as part of the inauguration

of their new Sibelius Hall.

The orchestra is slimmed down and the six percussionists provide a marvellous

range of sonorities and rhythms throughout. The first movement – Untitled

– is also strangely unformed at the outset, with the quietest of introductions

emerging from the primordial silence.

It’s another of those captivating moments one has come to expect from

this composer, the spacious acoustic allowing the music to bloom and

grow with ease.

Even with a reduced orchestra Aho manages some powerful percussive climaxes

but that theatricality is tempered by a commendable economy of style.

The emerging rhythms take some time to establish themselves but when

they do they come across with tautness and precision. The music then slips seamlessly into a gentle Andante. The heckelphone

is soon supplanted by vital, thrusting rhythms one usually associates

with Bernstein in Broadway mode. As for the Kroumata ensemble they are

a class act, their competing rhythms very well articulated and recorded.

Sample the passage that begins at 8:44 and you’ll get some idea of the

extraordinary virtuosity of these players.

The final movement – Tranquillo – harks back to the quiet opening of

the symphony. More than that, it looks forward to the Twelfth Symphony

in its use of space. Here the percussionists are arrayed around the

hall, the distinctive sound of the 10-stringed kanteles – traditional

zither-like instruments – adding to the disembodied swirl of this movement.

In

a theatrical flourish reminiscent of Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ Symphony Aho

directs the percussionists to leave the hall, playing ancient cymbals

as they go. Granted, a multi-channel recording would probably capture

the shifting aural perspectives more effectively – as indeed it does

in the Twelfth Symphony – but it’s still a wonderful sign-off.

Symphony

No. 12 ‘Luosto’ (2002-03) [48:56] I. The Shamans [13:16]

II. Winter Darkness and Midsummer [14:00] III. Song in the

Fells [9:36] IV. Storm in the Fells [11:06] Taina Piira (soprano)

Aki Alamikkotervo (tenor) Lahti Symphony Orchestra and Chamber Orchestra

of Lapland/John Storgårds rec. March 2007, Sibelius Hall, Lahti,

Finland

Symphony

No. 12 ‘Luosto’ (2002-03) [48:56] I. The Shamans [13:16]

II. Winter Darkness and Midsummer [14:00] III. Song in the

Fells [9:36] IV. Storm in the Fells [11:06] Taina Piira (soprano)

Aki Alamikkotervo (tenor) Lahti Symphony Orchestra and Chamber Orchestra

of Lapland/John Storgårds rec. March 2007, Sibelius Hall, Lahti,

Finland  BIS SACD 1676 [48:56]

BIS SACD 1676 [48:56]

Just as the finale of Aho’s Eleventh Symphony owes something

to Haydn the Twelfth draws on an earlier tradition of outdoor

music. The most familiar examples of this are Handel’s Music for

the Royal Fireworks – itself the model for Sir Malcolm Arnold’s

Water Music, Op. 82 – and Haydn’s Feldparthien, but rather

than a barge or castle grounds Aho chose to set his work on a mountainside.

The

CD booklet has a fascinating photograph of the premiere (click to enlarge),

also conducted by John Storgårds, on the wooded slopes of Mount

Luosto, in Finnish Lapland. The BIS recording was made in the now familiar

Sibelius Hall, with the large orchestra and chamber forces placed on

opposite sides of the auditorium. The latter are joined by the saxophone

and soprano soloist, with various brass and percussion instruments arranged

around the periphery. Of course it’s only an approximation of the open-air

version, which must have been extraordinary, but this multi-channel

SACD does offer the listener a genuine ‘surround-sound’ experience.

The two-channel stereo layer gives you a fair idea of the spatial nature

of this symphony, but this is one work that really demands a multi-channel

system to maximise the effect.

The

CD booklet has a fascinating photograph of the premiere (click to enlarge),

also conducted by John Storgårds, on the wooded slopes of Mount

Luosto, in Finnish Lapland. The BIS recording was made in the now familiar

Sibelius Hall, with the large orchestra and chamber forces placed on

opposite sides of the auditorium. The latter are joined by the saxophone

and soprano soloist, with various brass and percussion instruments arranged

around the periphery. Of course it’s only an approximation of the open-air

version, which must have been extraordinary, but this multi-channel

SACD does offer the listener a genuine ‘surround-sound’ experience.

The two-channel stereo layer gives you a fair idea of the spatial nature

of this symphony, but this is one work that really demands a multi-channel

system to maximise the effect.

This is also perhaps the most Sibelian of Aho’s symphonies, in that

it taps into Finland’s primeval past, a time of dark superstitions and

wild, untamed landscapes. Of course sacred mountains played a central

part in this pagan world, so it’s entirely appropriate that Aho should

choose the title ‘Luosto’ for this symphony. Indeed, the first movement

– ‘The Shamans’ – makes this ritualistic link with some of the most

ferocious drumming imaginable. Anyone who has heard the Kodo drummers

of Japan will have an inkling of what to expect here.

(In his detailed and entertaining liner-notes Aho admits he considered

the barrel-like Japanese o-daiko drums but settled for traditional

bass drums instead.)

It’s powerful, visceral music laced with moments of genuine beauty and

sweep, as in the passage that begins at 3:13. There is grandeur, too, as befits the mountain setting, the two

bands playing with enormous energy – listen to that crescendo at 7:20.

The use of rain sticks and other exotic instruments make for an exotic

and overwhelming musical experience.

There is much more to this symphony than brute force – as the eloquent

close of ‘The Shamans’ confirms – and in the second movement we pass

into a world of contrasts, winter night and summer light. In the first

half eerie brass echo, as if in a void – Haydn’s ohne Form und leer,

perhaps – and a blazing es ward licht as the sun appears at 4:10.

What follows is music of haunting beauty, superbly played and recorded.

By

whatever yardstick one might choose this is a composer at the height

of his powers – confident, forthright, original – and the closing pages

of this movement are as memorable and moving as anything one might expect

from Sibelius or any of the great symphonists.

The wordless vocalises of the tenor and soprano soloists dominate ‘Song

in the Fells’, a celebration of the open spaces painted in glowing orchestral

colours. As pastoral music goes there is nothing hackneyed here, thanks

to Aho’s seemingly inexhaustible palette.

But even in this idyllic setting there is some discord – a hint of the

coming storm at 4:56 – and I imagine many listeners will think of Berlioz’s

‘Scene aux champs’ at this point. Needless to say the soloists both

sing with great ardour, their voices carrying across the wide open spaces.

‘Storm on the Fells’ must have made quite an impact on the mountainside

with its distant rumbles of thunder. Richard Strauss’s Alpine drenching

is something of a benchmark in ‘storm music’ but Aho’s is a more subtle

affair, built over a longer span and with tension building superbly

along the way. He also uses wind machines, the singers all but drowned

out by the ferocious weather. And at 4:29 there is another of those

frisson-making drum-led crescendos before the thundering orchestra and

cracks of lightning give even Herr Strauss a run for his money.

In the Alpine Symphony the music that follows the storm is the

most lovely; and so it is here, beginning at 7:34. The soloists return

and there is a real sense of renewal and optimism as the work draws

to a quiet but radiant close.

‘Luosto’ is simply wonderful and will be one of my discs of the year.

It sets the bar very high, though, and I just wonder how Aho can possibly

reach it – let alone clear it – with his next symphony. It would certainly

be an ideal Prom piece, well suited to the Royal Albert Hall. Now I

would beg, borrow or steal a ticket for that....

Concerto

for tuba and orchestra (2000-01)* [28:30] Concerto for contrabassoon

and orchestra (2004-0)** [34:22] * Øystein Baadsvik (tuba)

* Norrköping Symphony Orchestra/Mats Rondin **Lewis Lipnick (contrabassoon)

**Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra/Andrew Litton rec. 23 & 24 February

2006, Grieg Hall, Bergen, Norway (contrabassoon concerto); November

2006, Louis de Geer Concert Hall, Norrköping, Sweden (tuba concerto)

BIS CD 1574 [63:42]

Concerto

for tuba and orchestra (2000-01)* [28:30] Concerto for contrabassoon

and orchestra (2004-0)** [34:22] * Øystein Baadsvik (tuba)

* Norrköping Symphony Orchestra/Mats Rondin **Lewis Lipnick (contrabassoon)

**Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra/Andrew Litton rec. 23 & 24 February

2006, Grieg Hall, Bergen, Norway (contrabassoon concerto); November

2006, Louis de Geer Concert Hall, Norrköping, Sweden (tuba concerto)

BIS CD 1574 [63:42]

Andrew Litton isn’t a conductor I readily associate with contemporary

music so I was curious to hear what he’d make of this oddball concerto

for contrabassoon. As for the tuba concerto, yes, there are others –

by Ralph Vaughan Williams and a number of contemporary composers – but

I’m not aware of any written for contrabassoon. In any event Aho made

a point of familiarising himself with this duo’s strengths and weaknesses

before putting pen to paper.

The Norwegian tubist Øystein Baadsvik is an obvious choice for

this recording, given that he has premiered some 40 works for the instrument.

In his liner-notes the composer speaks of the tuba’s ‘songful’ qualities

and that’s certainly borne out by the first entry in the Andante. Aho

tends to focus on the tuba’s more liquid middle register here, but the

instrument’s rasp and bray is unmistakable in the passage that begins

at 3:49. That said, Baadsvik plays with great accuracy, whatever the composer’s

demands, and he is given an excellent recording to boot.

Mats Rondin and the Norrköping orchestra are both new to me and

as good as they sound I longed for the Lahti band’s authority and special

brand of magic in this music. I certainly can’t fault the orchestra’s

virtuosity in the Allegro, even if they do sound a little undernourished

at times. No such qualms about the soloist, who is nothing short of

heroic – sample the passage beginning at 3:50 – producing some glorious

sounds along the way.

The pizzicato strings that open the Larghetto are well caught, the tuba’s

first quiet entry astonishingly secure. I was reminded that this gruff,

vaguely comical instrument can actually play cantabile, a quality

the composer seems to encourage here. Listen to the passage at 7:00

and you’ll hear some of the strangest and most original noises you’re

ever likely to hear from a tuba. Not since the Tetraphonics disc of

saxophone pieces have I heard the sound of a brass instrument so artfully

exploited.

A thoroughly enjoyable concerto, superbly played and recorded. By the

end any small misgivings I may have had about this band – and indeed

this concerto – simply evaporated. Well worth hearing and certainly

deserving of a place in the concert hall.

The traditional contrabassoon has a number of weaknesses, many of which

were addressed by the Fox instrument released in 2001. Designed by the

New York Philharmonic’s Arlen Fast the new system of octave keys improved

the instrument’s upper reach and tackled issues of poor articulation

and uneven tone. According to the instrumentarium in the CD booklet

– a useful touch – the concerto’s dedicatee, Lewis Lipnick, uses one

of these improved instruments.

Lipnick and the Bergen Philharmonic gave the first performances on 23rd

and 24th February 2006, which form the basis of this live

recording. From the brooding start of the first movement – marked Mesto

(sadly) – it’s clear the new system results in a cleaner, more secure

sound, even in its mournful lower registers.

Aho claims this is one of his most 'monumental’ concertos and it certainly

grows to an imposing climax in the first movement. Litton builds the

tension very well indeed and the orchestra sound suitably rich and sonorous.

From 6:40 onwards one hears just how lyrical this new instrument can

sound; very beguiling indeed. And there is no problem with articulation or volume either, as it’s

perfectly capable of holding its own in percussive company.

This is an imaginative and varied piece, with some outstanding playing

from all quarters. Litton, who doesn’t always strike me as the most

charismatic of conductors, certainly has the measure of this work, especially

the contrasts of the trenchant second movement. And just listen to Lipnick’s

low notes at 3:14; very impressive indeed.

The final movement, Misterioso, which sounds like a lament at times,

reminds me a little of Shostakovich. Here, more than anywhere else this

work sounds less like a concerto, the orchestra underpinning and complementing

the soloist. The ending is muted, resigned even, the soloist fading to silence.

There is no applause – indeed it’s hard to believe there is an audience

there at all.

The BIS team have done a very good job of conveying the special feel

of a live performance without compromising on sound quality. There’s

certainly no sign of the slightly ‘dead’ acoustic one often gets with

a hall full of concertgoers. A very desirable disc that increases one’s

admiration for these under-rated instruments and their players.

Quintet for Oboe and String Quartet (1973)* [29:13] Seitsemän

inventiota ja postludi (Seven Inventions and Postlude) (1986/1998)**

[15:34] Quintet for Flute, Oboe, Violin, Viola and Cello (1977)†

[18:56] Sinfonia Lahti Chamber Ensemble *Jukka Hirvikangas (oboe), Jyrki

Lasonpalo (violin I), Esa Heikkilä (violin II), Anu Airas (viola),

Ilkka Pälli (cello) ** Jukka Hirvikangas (oboe), Ilkkä Palli

(cello) †Outi Viitaniemi (flute), Lasse Junttila (oboe), Jaakko Kuusisto

(violin), Anu Airas (viola), Ilkka Uurtimo (cello) rec. March 1999,

Kuusankoski talo, Kuusankoski, Finland; May 1999, Ristinkirkko, Lahti,

Finland BIS CD 1036 [64:51]

We go right back to the beginning of Aho’s musical career with the first

quintet on this disc, composed in 1973. In his booklet notes Aho confesses

his love for the oboe; as with the tuba in the Tuba Concerto,

he took the trouble to familiarise himself with the oboe's capabilities,

the idea being to ‘extend the instrument’s expressive range’.

The first of the two movements opens with a bright, songful introduction

on the oboe, soon underpinned by the warm strings.

As with the orchestral works there is a remarkable clarity to the writing

and a real sense of musical purpose. Even in the extended and more animated

passages there is a lively dialogue between oboe and strings, at times

building to moments of great intensity.

Fortunately the engineers have found a good recording balance, so the

oboe never sounds overbright, even when played in extremis (at

10:18, for example). Which is just as well, as this instrument is the

dominant force in this partnership. Just listen to the birdlike figures

in the passage beginning at 5:39 and the virtuosic playing that follows.

For a composer still at the beginning of his career this is assured,

confident stuff. And the strings play with great bite and passion in

the exhilarating section that begins at 9:43.

The first movement cadenza is even in tone and very clearly articulated,

whatever the register. Jukka Hirvikangas is certainly the master of

his instrument, and that goes for the nimble rhythms of the second movement

– listen to the breathtaking passage that begins at 2:32. There is much to savour here, and although the oboe’s expressive

range is tested it’s only in the second movement that the overall mood

darkens and the music becomes more inward than extrovert. That said,

Aho brings in some wonderfully sensuous, rather Latin, rhythms at 11:18.

But the day belongs to the oboist, whose virtuosity is simply astonishing,

now ebullient now reflective but always crisp and clear.

Seven Inventions is a much later work, derived from one of Aho’s

earlier ones, the chamber opera Avain (The Key). The movements,

played without a break, show the composer in a more austere, astringent

mode, the music pared down to its essentials. Sonorities and colours

are also darker and more complex, although Hirvikangas’s bright-toned

oboe sings throughout.

In the melting fifth movement, marked Andante, he has the field to himself,

but in the sixth the mood suddenly changes. Ilkka Pälli’s cello

playing is especially dark and intense from here onwards. The final Postlude is one of those classic Aho movements that fades

to an enigmatic silence.

By contrast the shrill opening bars of the Quintet for Flute, Oboe,

Violin, Viola and Cello are altogether more bracing. The composer admits he set out to ‘explore the outer limits of virtuosity

in chamber music’, Outi Viitaniemi’s flute adding much to the music’s

somewhat febrile character. It has the usual vigour and rhythmic interest

we have come to expect from Aho but perhaps there’s more focus on colour

and timbre. Certainly he makes great demands on his players – sample

the rising passage at 3:54 – and the results are never less than compelling.

Indeed, for those who don’t like chamber music in general – and the

contemporary variety in particular – this piece has all the colour,

drama and thrust one could hope for, without ever becoming incoherent

or overbearing. I was impatient for the end, not through boredom but

because Aho usually springs some surprises in the final pages. Happily

this quintet is no exception; sample 15:00 onwards and you’ll hear music

of great originality and flair.

This is another welcome release, characterised by a bright, clearly

etched recording and playing of great polish. There’s always a fine

line between sheer virtuosity and musical substance but the balance

here seems just right.

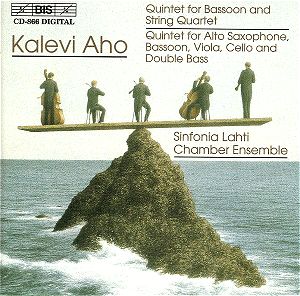

Quintet for Bassoon and String Quartet (1977)* [37:02] Quintet

for Alto Saxophone, Bassoon, Viola, Cello and Double Bass (1994)**

[32:36] Sinfonia Lahti Chamber Ensemble *Harri Ahmas (bassoon), Jyrki

Lasonpalo (violin I), Ulla-Maija Hallantie (violin II), Anu Airas (viola),

Ilkka Pälli (cello) ** Hannu Lehtonen (alto saxophone), Harri Ahmas

(bassoon), Anu Airas (viola), Ilkka Pälli (cello), Eero Munter

(double bass) rec. December 1997 (*) and December 1996 (**), Ristinkirkko,

Lahti, Finland BIS CD 866 [70:42]

Four years after the Quintet for Oboe and String Quartet Aho

wrote one to showcase the talents of Juhani Tapaninen, the Finnish Radio

orchestra’s solo bassoonist. Like the Seven Inventions it is

cast in several movements, played without a break, and it also has a

clear, overarching narrative.

The Ouvertüre starts comically enough, with instrumental brays and

slides, the overall sound bright and clear. The Gershwin-like melody

played over pizzicato strings is particularly memorable as is the one at the beginning of ‘Parodie’, the second movement.

There is a bluesy languor at this point, but more than that it’s a deft

piece of pastiche on Aho’s part.

There are some harmonically dense and complex passages here, with pizzicato

strings sounding surprisingly vehement, followed by a lighter, freewheeling

Scherzo. There is plenty of wit and buoyancy in this music, which demands

great precision and unanimity from the Lahti players. This is clearly

one of those occasions where one senses the musicians enjoying themselves;

just sample the strings’ bracing attack at 4:28.

The Cadenza is another of those virtuosic movements that manages to

combine bravura playing with a modicum of feeling. Some wonderfully

assured playing here, especially from the strings, and bassoonist Harri

Ahmas makes the unwieldy lower notes seem surprisingly well rounded

and well projected. And what a wistful conclusion, thanks to cellist

Ilkka Palli’s generous, warm-hearted playing.

The Finale is light and airy, textures admirably clear throughout, the

bassoon proving it is more agile than one might expect.

And in Epilog Aho moves from a stentorian opening through a kaleidoscope

of colours and Morse-like blasts from the bassoon to a quiet, spare

close, complete with strangely muted string pizzicatos.

The alto sax is in charge of the second quintet on this well-filled

disc, its distinctive timbre ringing out from the very start. The instrument

doesn’t sound as bluesy as one might expect, more like another colourful

thread to be weaved into this musical tapestry. The double bass makes

a considerable impact in the first movement, ballast to the high-flying

sax – just sample the passage beginning at 3:00 and marvel at Hannu

Lehtonen’s transported playing.

And what to make of those jaunty rhythms beginning at 8:16 and 8:50?

Aho again proves he is adept when it comes to slipping from one mood

or mode to another, making it all sound so natural and seamless.

The first movement is so packed with incident – after all, it lasts

nearly 18 minutes – one might be tempted to think there’s nothing left

to say in the remaining two. Not so, although the opening of the Allegro

is as insistent as that of the Largo. Aho manages to get so much weight

and momentum out of his players at this point that it’s sometimes difficult

to believe there are only five instruments in the mix.

This is certainly the composer at his motoric best, repetitive yet always

gripping. Just listen to that fevered blast on the alto sax at 3:26

– hair-raising.

The Andante contains some arresting sounds, from the brooding intro,

complete with wailing sax, to the more impenetrable thickets that follow.

There is so much material here one might feel a little bewildered, and

while the musicians have a firm grip on the music I did find myself

wandering towards the end. Perhaps the sheer virtuosity of the piece,

remarkable as it is, becomes a little relentless after a while.

I imagine most listeners will come to Aho through his orchestral works

which, in my view, show this composer at his considerable best. As for

the chamber pieces these might well ensnare those who don’t usually

warm to the genre, as they have a symphonic weight and logic about them.

For those who already know the symphonies they make an interesting appendix

to this composer’s other works and, as such, should be included in your

collection.

Review index

September 2008/updated July 2018