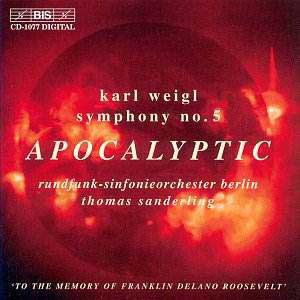

Like Korngold's only Symphony (wonderfully done by James de

Preist and the Oregon Symphony on Delos) Weigl's Fifth is dedicated to

the memory of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (who died in April 1945). This

tribute to the President of the country that had provided refuge to these

two fluchtlings reflected the affection and high respect in which

they held their saviour country.

Weigl was double-damned in 1930s Vienna - both a Jew

and a Socialist. He had been fêted until the Nazis came to power.

When it came his fall was complete.

As Lloyd Moore's fine notes point out we can now gradually

gain a truer and broader perspective on the range of German music of

the first half of the last century. Korngold, Pfitzner, Schmidt, Weill,

Hessenburg, Schoenberg, Zemlinsky, Schreker and Hartmann can be only

loosely arranged in 'schools'. The 'what ifs' such as Rudi Stephan (1887-1915),

and Heinrich Bienstock (1894-1918) might well have further transformed

the scene but their lives were cut short by the Great War. These two

were, in potential, equally as significant as George Butterworth, Cecil

Cole (celebrated in a recently released Hyperion CD) and Ernest Farrar

(Chandos).

Weigl is not a perfect fit with any school. The closest

match is with Bruckner and up to a point with Franz Schmidt. Schmidt

provided his own apocalyptic 'symphony' in the shape of The Book

with Seven Seals which predated the Weigl symphony by about a decade.

Schmidt captures the ghastly and awesome horrors of the pestilential

horsemen with a keener blade than Weigl (compare the Weigl's finale

entitled 'The Four Horsemen'. The axle and anchor of this work is the

Adagio which, at 15.25, is only seconds shorter than the Evocation

first movement. The Adagio proclaims lineage direct to the adagios

of Bruckner's last two symphonies, especially the Eighth. It is a serene

iron and chainmail paean to tragedy. Powerful and eloquent, this is

a statement shot through with golden strands represented by the soulful

brass. The Brucknerian manner, this time, in craggy mode is also encountered

in the finale. So, just when you have made up your mind about this symphony

let me also mention how it starts. The score instructs the orchestral

musicians to enter and tune up (all as an integral part of the work)

then the conductor appears and cues three trombones and a tuba on a

raised platform. Some of the hyper-lyrical manner of Franz Schmidt from

the Second Symphony can be heard in the first movement.

Sanderling and the Berlin orchestra are dedicated though

I sensed a vague hesitancy in their playing which is not found in the

tape of Stokowski rehearsing the American SO for the 1968 premiere.

Such transient issues (completely absent from the great adagio by the

way) are nowhere to be found in their reading of the Intermezzo

(initially the first movement of the Second Symphony). It is a flighty

work with hints of Prokofiev and Dukas and with flashes of Bruckner

along the way. The work has some kinship with the Comedy Overture

recorded by his pupil Peter Paul Fuchs with the Baton Rouge Symphony

[concert recordings only -unpublished]. Fuchs was not the only one to

record Weigl. Fellow Vienna University student Frederic Waldman recorded

the Weigl Violin Concerto with Sidney Harth and the Musica Aeterna orchestra

in LP days.

We now need a complete set of the six symphonies. BIS

have made an auspicious start.

Rob Barnett

Gwyn Parry-Jones has also listened to this disc

Composers expend a tremendous amount of inspiration

and perspiration on the openings of works, particularly big, public

statements such as symphony, oratorio or opera. Thus Karl Weigl’s Fifth

Symphony, the Apocalyptic, begins with the orchestra tuning up; the

conductor enters while this is happening, and signals to the brass,

who intone a fanfare both angular and portentous. This is a stunning

coup de théâtre, then; but such gestures have their serious

drawbacks. The rest of the work has to live up to the level thus set,

and we can all name works with wonderful openings which don’t quite

bring it off. The best-known ones, in my book, are probably Strauss’s

Also Sprach Zarathustra and Vaughan Williams’ Sea Symphony – any additions?

I fear that Weigl doesn’t manage to satisfy the great

expectations he arouses either. There is not a single gesture in this

symphony of 1945 which is anywhere near as radical and shocking as the

opening, and therein lies the problem. The piece is in fact, for its

time, a relatively conservative piece, its style unashamedly deriving

from late Romantic German models. It has many beautiful and striking

moments, but in a different sense from that extraordinary commencement.

Weigl was an Austrian Jew, who as a young man worked

with Mahler at the Vienna Opera, regarding his years there as the most

instructive of his life. During the Nazi years, he was, like so many

Jewish artists, gradually blanked out, and, seeing the writing on the

wall, he left for the USA in 1938, where he remained for the rest of

his life. This symphony, composed during the darkest years of World

War II, was dedicated to Franklin D. Roosevelt, in gratitude for providing

the composer with home and refuge.

There are four movements; the first, entitled ‘Evocation’,

settles down into a broad, complex discussion, based on the brass fanfare

theme mentioned above. The second, in the place of a Scherzo and called

‘The Dance around the Golden Calf’, seems a little tame for its title,

inevitably calling to mind comparisons with Schönberg’s piece of

the same title in Moses und Aaron. The latter is able to fill

his work with a blood-curdling sense of wild abandon, while Weigl’s

is grotesque, almost comical at times, but nowhere near so convincing

in its portrayal of evil at work.

The slow movement, ‘Paradise Lost’, is for me the most

convincing, having many passages of great expressive beauty and intensity,

as well as an ethereal coda, where the ghost of Mahler is felt near

– compare this ending to the closing bars of the first movement of the

latter’s 10th Symphony, for example. The finale, ‘The Four

Horsemen’ (of the Apocalypse, one presumes), again seems too mild to

live up to its title, and, like all the movements, tends to go on too

long for its material.

The Phantastisches Intermezzo contains probably

the most convincing music on the disc. This is from 1921, the ‘Austrian’

part of Weigl’s composing career, as the informative booklet notes describe

it. Like the symphony, it is rather protracted, but here, the material

and the imaginative impulse seem to last the distance far better. This

is the music of a composer still very much ‘in touch’ with the music

of his time, and the detailed orchestration has a French brilliance

to it – I was reminded very much of Dukas – while the Romantic horn

fanfares and chorale-like string passages once more recall Mahler. This

is a movement that might justifiably find its way into the occasional

repertoire of symphony orchestras.

Sanderling and the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra

perform manfully, with much fine individual playing from wind section,

and rich, disciplined strings. The recording is clear, but doesn’t produce

a convincingly integrated tutti sound, which means that some of the

imposing climaxes carry less weight and conviction than they need.

Gwyn Parry-Jones

ALSO TRY:-

String Quartet No. 4, viola sonata and songs - Special Limited Private

Edition of 1000 2CD box-sets 50th Anniversary Commemorative Recording

KARL WEIGL FOUNDATION KWF991001-2 [56.25+58.42]

Copies of this limited edition set can be ordered from:

The Karl Weigl Foundation

901 E. Street #300

San Rafael, CA 94901

phone +1 415 526-2043

fax +1 415 526-2075

kweigl@brsgroup.com