Having lived with these piano sonatas for some time before

preparing this review, I can say that, in my opinion, these three works

are of very considerable stature … even greatness. They are perhaps the

most significant additions to the repertoire in the second half of the

20th Century. So there, I’ve said it. The only problem is I

don’t think I like them … and why? Because they constantly challenge the

listener. They are never or rarely easy listening. They are never easy

playing. Even when not technically difficult they are emotionally charged

or they demand a particular touch or sensitive pedalling. Sometimes, as

with the opening of the 1st Sonata, they are so delicate that

they are almost too sensitive to speak. Sometimes, as with the great climax

of the 2nd Sonata, they are so violent and loud as to appear

to be out of control with anger.

Another typical Schnittke mannerism is the charming

and delightfully tuneful way he may begin a movement. Examples include

the second movement of the 2nd sonata or the first movement of the 3rd

sonata. Listen too to the little melody which begins the 2nd

movement of the 1st sonata, and then watch and listen whilst

the melody is destroyed systematically and wastes away into a black

hole.

The 1st sonata, in four movements, lasts

over thirty minutes and makes considerable demands on the listener.

The 2nd is in three movements and lasts less than twenty

minutes. It makes many technical demands on the pianist. The 3rd

sonata in four movements makes heavy demands on everyone but seems to

me, in its concentrated span of just fifteen minutes, to be the finest

of the three works; that is not to decry the first two. Each is dedicated

to a different pianist. The dedicatee of the second is the composer’s

wife, Irena.

The booklet notes by Ewa Burzawa, which are translated

from the German, are quite excellent. I could have quoted great chunks

from them in this review. Any music lover would grasp their meaning

and learn much in the process. There is an introduction to Schnittke

himself then some helpful and not too technical advice as to the way

it is best to listen to these complex works. There is no doubt that

these notes open the door of understanding of some of the technicalities.

This is necessary if the music is to be more deeply grasped. How true

it is that Schnittke "upheld the classical forms which always predominated

in Russian or Soviet music – even if only in variant form or as an allusion

to them". I think she might even be referring to the 3rd

Sonata’s second movement where, one might suggest, the Allegro marking

is a reference to a classical Scherzo movement. That is certainly the

way it seems to me.

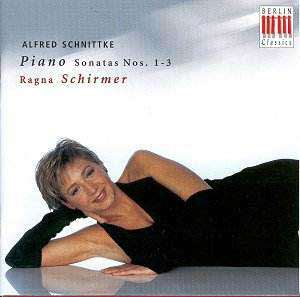

I cannot speak too highly of pianist Ragna Schirmer.

Curiously enough, though not inappropriately, she is something of a

Bach specialist. She has adapted the necessary precision and anti-Romantic

touch perfectly to Schnittke. I have never heard anyone else play these

pieces, and other interpretations would throw some fascinating insight

onto the myriad possibilities inherent in these scores. Nevertheless

Schirmer is superb, not always helped by the rather brittle recorded

sound of the top register which Schnittke regularly demands.

There is a consistency of language in these pieces

and a distillation of sonata writing technique in the five or so years

which cover their composition. They have integrity. Ultimately, future

generations may well come to regard them as benchmarks in the piano

literature of the late 20th Century.

Gary Higginson