S & H International Opera/Festival Review

Salvatore Sciarrino, Macbeth (U.S. Premiere), Oper Frankfurt, Ensemble Modern, John Jay College Theater, New York, NY, July 9, 2003 (BH)

Salvatore Sciarrino: Composer and Librettist

Achim Freyer: Director and Set Designer

Friederike Rinne-Wolf: Co-Director

Jonannes Debus: Conductor

Gerd Budschigk: Lighting Designer

Amanda Freyer: Costume Designer

Klaus-Peter Kehr: Dramaturg

Cast:

Sonia Turchetta: Sergeant, Banquo‚s Son, a Murderer, a Carrier

Annette Stricker: Lady Macbeth

Otto Katzameier: Macbeth

Richard Zook: Banquo, the Spirit, an Attendant

Thomas Mehnert: Duncan, a Courtier, Macduff

Vocal Ensemble:

Gabriele Hierdeis, Barbara Ochs, Vanessa Barkowski, Christoph Hierdeis, Johannes Schendel, Helmut Seidenbusch

In program notes written for the Schwetzingen Festival, Salvatore Sciarrino wrote, "Nothing builds and arouses like theater with a new language" and throughout this astonishing production, I could not stifle amazement at just how effectively his vision did precisely that. This is not the exhilarating, kinetic bloodbath of filmmaker Roman Polanski, nor the swift drama of Verdi’s version (which the Kirov Opera will present this weekend, also as part of the far-reaching Lincoln Center Festival).

No, this is an eerily quiet, introspective Macbeth, in Sciarrino’s own distinctive, minutely calibrated language. It is a beautiful score, filled with barely fluttering movement, some of it almost at the threshold of hearing (his Luci Mie Traditrici was presented here in 2001.) Echoing Webern, Kurtág, and others, the sound palette is compiled from tiny gestures, often sparely written, and interpreted here by the formidable Ensemble Modern.

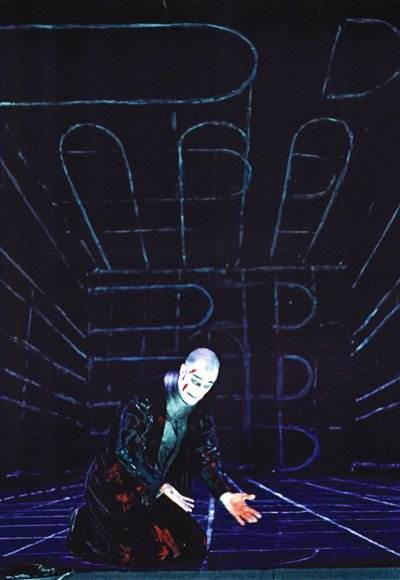

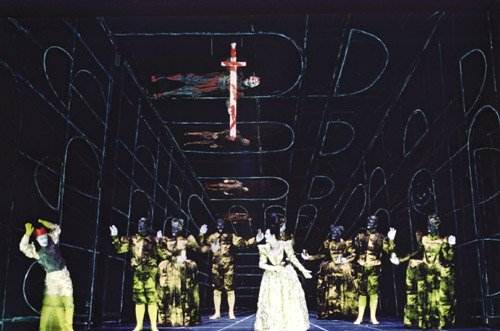

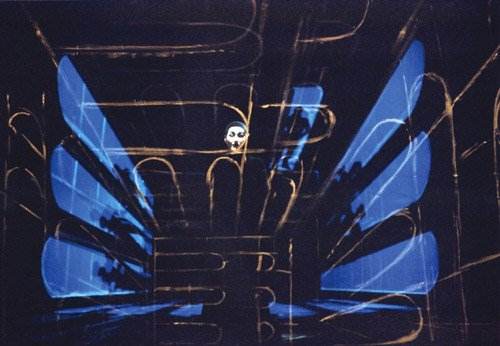

The gorgeous set, by director Achim Freyer, was in a way simply conceived, yet almost palpably disorienting. Inspired by drawings of the architect Jan Vredeman de Vries (1527-1604), Freyer’s initial image was a charcoal-colored scrim with white lines converging in the distance, creating what appeared to be a vast hallway. However, when the lighting eventually crept up softly behind it, a three-dimensional version appeared, precisely positioned to match the two-dimensional one. The walls were covered with rows of De Chirico-esque arched apertures, shrinking smaller and smaller in an extreme perspective, culminating in three tiny doorways, seemingly far in the distance.

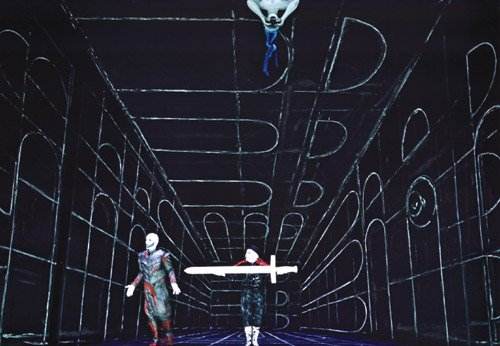

Combined with this hallucinatory funhouse, some of the stagecraft was absolutely startling. At one point Macbeth appeared to walk down the left wall, his body parallel to the floor. (And make no mistake, he was singing in this position, also.) Lady Macbeth made a similar entrance, rising up horizontally from the floor on the left side. But later the back wall became the floor, as if we were now gazing down from high above, with silhouettes of cast members visible in the tiny windows far below.

As Lady Macbeth, Annette Stricker evoked Elsa Lanchester in Bride of Frankenstein with ghostly white makeup and a huge spear of black hair. Her sleepwalking scene was completely riveting, even if it probably tested the patience of some. With her spot-lit head appearing to float in center stage, flanked by six members of the chorus crouched in niches in the walls, she delivered her mesmerizing monologue with everyone onstage virtually motionless. It will be difficult to see any future depiction of the character without recalling Stricker’s frozen, ecstatic smile.

In the title role, Otto Katzameier sang with remarkable beauty, coupled with Kabuki-like discipline and body control. This was a brooding Macbeth, immersed in constant inward torment, perhaps to the point of numbness. Even the final sword fight with Macduff was staged with icy formality, rather than physical carnage. Freyer and his brilliant lighting designer, Gerd Budschigk, created a strange and upsetting environment where people have been hypnotized and anesthetized by violence.

The hard-working cast outdid themselves in the demanding score with its constricted vocal range, deploying a highly compressed volume level for most of its two hours, unusual in a work of this scale. Even the witches, crouching in dimly lit openings in the upper right of the set, added to the mood, slowly flexing sets of long, bony fingers. (Think of the Alien films, with the creature coiled in languorous anticipation.) Thomas Mehnert memorably played Duncan as well as Macduff, and tenor Richard Zook also made the most of his multiple roles, especially Banquo, whose entrance was accompanied by brief passages from Don Giovanni heard through Sciarrino’s glistening prism.

In this striking scene and elsewhere, the exuberant Ensemble Modern, led by Johannes Debus, easily negotiated the composer’s unusual sonic effects. When Macbeth hears a knock on the door, it is more ominous because it is difficult to identify exactly what instruments are involved.

Entering this dark, quiet wonderland occasionally requires some concentration, and an above-average willingness to listen carefully. For much of the three acts (performed without intermission), I could feel my brain adjusting incrementally to the exaggerated and continually shifting perspective. And then, for some time afterward I felt a bit light-headed, exiting this claustrophobic hall of mirrors and settling back into the outside world.

Despite a handful of patrons who left early, most of the opening night audience seemed to be keenly involved, sitting quietly with Sciarrino’s pristine rustlings -- and nary a mobile phone to break the spell. Among the evening’s many strengths was the demonstration that this classic story can undergo almost a complete emotional transformation, into an almost serene tale filled with understatement and delicate moments -- quite a provocative idea.

Bruce Hodges

subject: Salvatore Sciarrino "Macbeth"

artist: Oper Frankfurt & Ensemble Modern

season: Festival 2003

photo credit: Monika Ritterhaus

description: Salvatore Sciarrino's "Macbeth," U.S. Premiere, Oper Frankfurt

& Ensemble Modern, July 9-12 at 8:30 p.m., John Jay College Theater

Return to:

Return to: